06 Gennaio 2018

Fonte: Texas Histocial Commission

Blog

Menu

Donate

Japanese, German, and Italian American Enemy Alien Internment

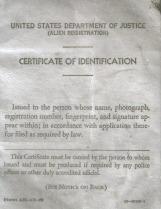

Enemy Alien Internee Registration Card (cover)

Shocked by the December 7, 1941, Empire of Japan attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii that propelled the United States into World War II, one U.S. government response to the war (1941-1945) began in early 1942 with the incarceration of thousands of Japanese Americans on the West Coast and the territory of Hawaii. Approximately 120,000 Issei (first generation, Japanese immigrants) and Nisei (second generation, U.S. citizens) from the U.S. West Coast were incarcerated in War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps across the country–based on Executive Order 9066 (Feb. 19, 1942). Through separate confinement programs to the WRA, thousands of Japanese, German, and Italian citizens in the U.S. (and in many cases, their U.S. citizen relatives), classified as Enemy Aliens, were detained by the Department of Justice (DOJ) through its Alien Enemy Control Unit and, in Latin America, by the Department of State’s Special War Problems Division. Additionally, the U.S. Army held enemy aliens across the U.S. wherever the number of apprehensions was too few for the Immigration and Naturalization Service to operate a detention facility.

These “West Coast” internees shared a common loss of freedom with the thousands of Japanese, German, and Italian Enemy Aliens and their U.S. relatives detained in DOJ camps through the Alien Enemy Control Unit Program. The DOJ, through the Federal Bureau of Investigations, began to target suspect Enemy Aliens in the U.S. as early as the night of December 7, 1941. Both legal resident aliens and naturalized citizens who were suspect were targeted [alongside enemy aliens], as were their families.

Within days of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the DOJ took into custody several thousand Axis nationals (during World War II, the Axis Nations consisted chiefly of Germany, Japan, and Italy). Although not legally administered in each case, and often spurred by prejudices, the action was intended to assure the American public that its government was taking firm steps to look after the internal safety of the nation.

Early in 1942, the DOJ established a bi-level organization, which handled the individual cases of aliens enemies: The Alien Enemy Control Unit in Washington, D.C. and through Alien Enemy Hearing Boards with branches located in each of the federal judicial districts of the United States (in Texas boards were held in Houston, Dallas, El Paso, and San Antonio). Each Alien Enemy Hearing Board consisted of three civilian members from the local community, one of whom was an attorney. Representatives of the U.S. Attorney for that district, the INS, and the FBI attended each hearing as well. Alien Enemies taken into custody were brought before an Alien Enemy Hearing Board and were either released, paroled, or interned for the duration of the war. Within a few months, the United States looked toward the possibility of exchanging these Alien Enemies with Japan, Germany, and Italy.

Texas hosted three temporary detention centers for these detainees in Houston, San Antonio, and Laredo; three DOJ Enemy Alien confinement camps administered by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) at Crystal City, Kenedy, and Seagoville, and two U.S. Army “temporary detention stations” at Dodd Field on Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio and Fort Bliss in El Paso.

National Park Service Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program

Through three grants (awarded in 2009, 2010, and 2012) the THC has worked to increase the historical record of all five internment camps in Texas during World War II. These projects include a mix of onsite interpretation, new printed brochures, these new webpages; and for the Crystal City confinement site, an archeolgoical survey and National Register of Historic Places nomination.

Crystal City Family Internment Camp: Enemy Alien Internment in Texas during World War II

Fort Bliss, Fort Sam Houston, Kenedy, Seagoville, and Crystal City: Enemy Alien Internment in Texas during World War II

Department of State – Special War Problems Division

By the mid-1930s, the U.S. was concerned about possible Nazi infiltration into Latin America—and the danger this might pose for western hemispheric security. In early 1941, the Office of Strategic Services ordered its Latin American section to begin surveillance of “enemy aliens” in the southern hemisphere.

Map of Central and South American Nations that Participated in Enemy Alien Exchanges

In addition to the DOJ’s efforts to identify and intern enemy aliens within the U.S., the U.S. Department of State through its Special War Problems Division coordinated efforts to bring axis nationals from Latin America to the U.S. during World War II. During the war, the U.S. Department of State, in cooperation with 13 Central and South American countries and two Caribbean nations, worked to increase the security of the Western Hemisphere, especially the vulnerable and vital Panama Canal Zone.

With the U.S. focused on a two-front global war against the Axis Nations, security of Latin America was accomplished primarily through financial and material support––via programs such as the Lend-Lease Act––to participating Central and South American nations. At a conference of Western Hemisphere countries in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in January 1942, the U.S. called for the establishment of the Emergency Advisory Committee for Political Defense. This new security program was tasked with monitoring Enemy Aliens throughout Latin America. Enemy Aliens were required to register with the country they resided in, their ability to become citizens was significantly slowed, their travel freedom was limited, and they were not allowed to own firearms and certain forms of radio broadcasting equipment.

This process resulted with thousands of Axis nationals of Japanese, German, and Italian ancestry taken into custody by local officials, many of whom were legal citizens of the Latin American countries participating. While a number of those arrested were legitimate Axis sympathizers, most were not. Latin America-Japanese, German, and Italians and their family members that were deported from their countries to the U.S. were first held locally, before being deported. Detainees were held for the duration of the war, unless they participated voluntarily or were “volunteered” to be repatriated through the Exchange Process. Forcibly deported, these detainees were shipped to the U.S.––considered security risks, they were detained in internment camps across the U.S., including the three in Texas.

These Latin American internees provided the U.S. with an increased pool of persons for exchange with Japan and Germany, each of which held comparable numbers of U.S. and Allied personnel taken prisoner during the war. While en route to the U.S., these Latin Americans were stripped of their passports and declared “illegal aliens” upon arrival, a fact many former internees and historians have referred to as “hostage shopping” and “kidnapping” by the U.S. and Latin American governments, because they were to be used in the repatriation process with the Axis.

History has shown that the U.S.’ efforts were conducted not just to legitimately secure the region due to fears that Germany might seize power in Latin American countries or Japan might attack and occupy the vital Panama Canal Zone––essential to rapid passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans during the World War II––but also due to prejudice. There were Latin American and U.S. businessmen who begrudged the success of Japanese, German, and Italian nationals and the war provided an opportunity to remove this source of competition.

Many Latin American detainees were sent to the U.S. by Army transport ships through ports such as New Orleans, Louisiana. From here internees were transported by train to camps in Texas or elsewhere. Internees were required to wear a white tags attached to their clothes and luggage that served as their identification at all times during transit, to Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp.

Enemy Alien Clothes and Luggage Transit Tags

Repatriation Process

Between 1939 and 1945, the U.S. and its Allies suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties to the advancing Japanese and German armies across the globe. In addition to combat soldiers taken prisoner, U.S. and Allied civilians were cut-off overseas as country after country fell to the Axis. In an effort to safely return them, the U.S. began to negotiate with Japan and Germany in March 1942 to establish an official “Exchange Process (or Program).” During the “Exchange Process,” Spain served as the Protectorate Nation for Japan, and Switzerland served as Protectorate Nation for Germany. This “Exchange Process” began with governmental diplomats, including consulate and embassy staffs and their families in the Americas, but increased to include both civilians and severely wounded prisoners of war. The “Exchange Process” continued through 1942 and into 1943. The chartered Swedish ship, the SS Gripsholm was one of several ships that sailed from the U.S. with internees from INS camps across the U.S.

Read more about the Japanese, German, and Italian American & Enemy Alien Internment in the Handbook of Texas Online.

Video

War Relocation Authority (ca. 1943)